Researchers have developed a polymer construction impressed by a basic “Chinese language lantern” that may grow to be greater than a dozen curved, three-dimensional shapes when it’s compressed or twisted. These fast form transitions can be triggered remotely with a magnetic area, which makes the design appropriate for a lot of potential makes use of.

How the Lantern Construction Is Constructed

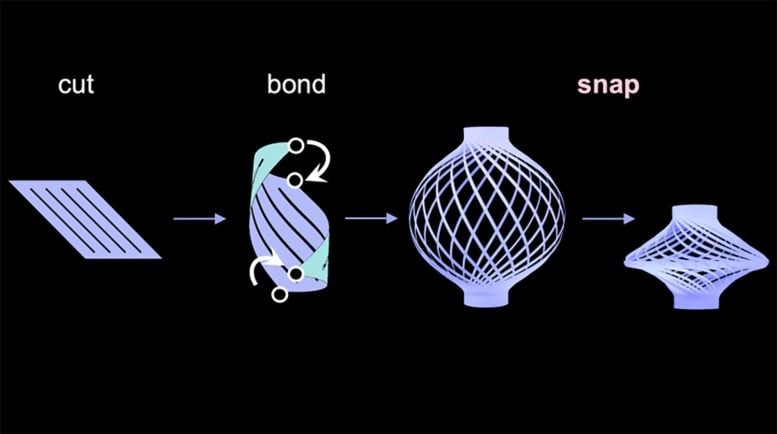

To create the lantern, the group started with a skinny polymer sheet lower into the form of a diamond-like parallelogram. They then added a row of evenly spaced cuts throughout the center of the sheet, producing parallel ribbons held collectively on the high and backside by stable strips of fabric. When the ends of those high and backside strips are joined, the sheet bends outward and takes on a rounded, lantern-like kind.

A Bistable Design With Saved Power

“This primary form is, by itself, bistable,” says Jie Yin, corresponding creator of the work and a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University. “In other words, it has two stable forms. It is stable in its lantern shape, of course. But if you compress the structure, pushing down from the top, it will slowly begin to deform until it reaches a critical point, at which point it snaps into a second stable shape that resembles a spinning top. In the spinning-top shape, the structure has stored all of the energy you used to compress it. So, once you begin to pull up on the structure, you will reach a point where all of that energy is released at once, causing it to snap back into the lantern shape very quickly.”

Twisting, Folding, and Multistable Variations

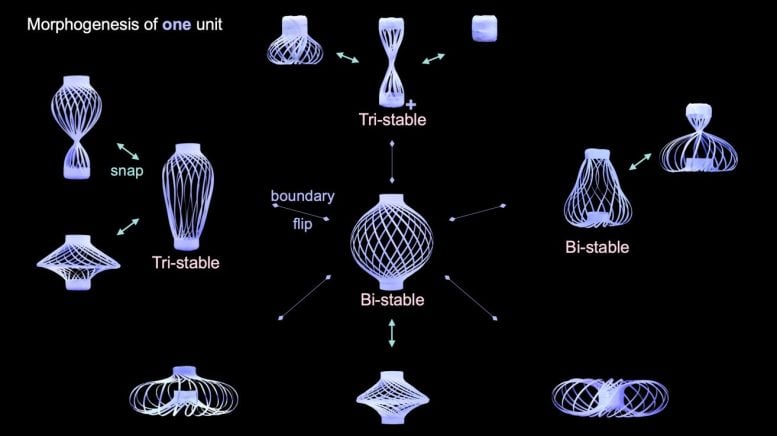

According to Yaoye Hong, first author of the paper and a former Ph.D. student at NC State who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, the team discovered that the lantern can be reshaped in many ways beyond simple compression. “We found that we could create many additional shapes by applying a twist to the shape, by folding the solid strips at the top or bottom of the lantern in or out, or any combination of those things,” Hong says. “Each of these variations is also multistable. Some can snap back and forth between two stable states. One has four stable states, depending on whether you’re compressing the structure, twisting the structure, or compressing and twisting the structure simultaneously.”

Remote Control and Real-World Demonstrations

The researchers also enhanced the structure by placing a thin magnetic film on the bottom strip of the lantern. This allowed them to twist or compress the design from a distance using a magnetic field. Several examples were demonstrated, including a gentle gripper that could hold a fish without injury, a water filter that opened and closed to manage flow, and a compact configuration that suddenly extended upward to reopen a collapsed tube.

Modeling Stability, Form, and Power Storage

To higher perceive how every model of the lantern behaves, the group developed a mathematical mannequin that describes how the geometry of the construction influences its form and the quantity of elastic power saved in every secure state.

“This mannequin permits us to program the form we wish to create, how secure it’s, and the way highly effective it may be when saved potential power is allowed to snap into kinetic power,” says Hong. “And all of these issues are important for creating shapes that may carry out desired purposes.”

Towards Future Metamaterials and Robotics

“Shifting ahead, these lantern models will be assembled into 2D and 3D architectures for broad purposes in shape-morphing mechanical metamaterials and robotics,” says Yin. “We will be exploring that.”

Reference: “Reprogrammable snapping morphogenesis in ribbon-cluster meta-units using stored elastic energy” by Yaoye Hong, Caizhi Zhou, Haitao Qing, Yinding Chi and Jie Yin, 10 October 2025, Nature Materials.

DOI: 10.1038/s41563-025-02370-z

The paper was co-authored by Caizhi Zhou and Haitao Qing, both Ph.D. students at NC State; and by Yinding Chi, a former Ph.D. student at NC State who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Penn.

This work was done with support from the National Science Foundation under grants 2005374, 2369274 and 2445551.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.