The march for voting rights from Selma, Alabama, to the capital of Montgomery in 1965 wasn’t meant to result in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. However then got here the horror of the scenes on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the place police fractured the late John Lewis’ cranium and beat organizer Amelia Boynton unconscious, with a lot of the violence caught on camera. It swayed public opinion: President Lyndon Johnson delivered the voting rights invoice to Congress quickly after, and it grew to become legislation on Aug. 6, 1965.

“So, we’ll transfer step-by-step — usually painfully however, I believe, with clear imaginative and prescient — alongside the trail towards American freedom,” Johnson said upon signing the invoice.

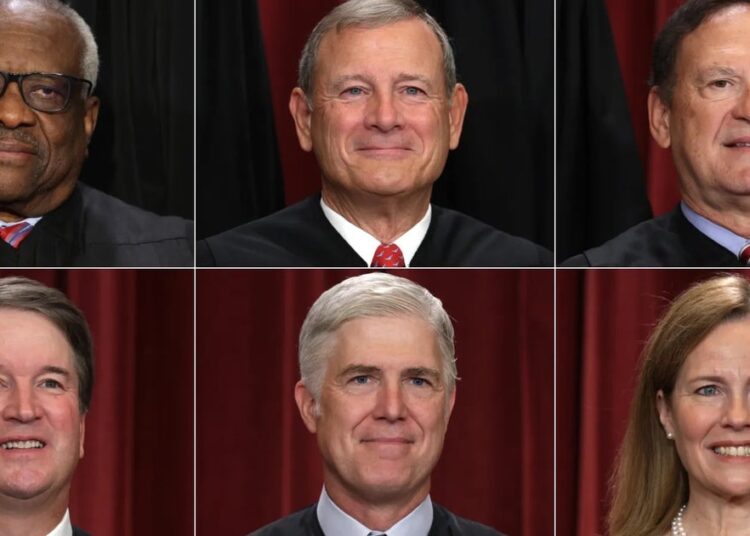

Sixty years later, opponents of the Voting Rights Act have moved step-by-step, usually painfully, backwards on that path. Within the palms of conservative opponents of voting rights, the Supreme Courtroom has subjected the Voting Rights Act to dying by a thousand cuts. A few of these cuts have been small, similar to limiting how courts take into account challenges introduced below the legislation. And a few have been giant, as within the 2013 choice in Shelby County v. Holder that ended the requirement for sure states with histories of discrimination to submit election modifications and district maps to the Division of Justice for approval.

Because the Supreme Courtroom delivers choices that can irrevocably alter our democracy, unbiased journalism is extra very important than ever. Your assist helps HuffPost maintain energy to account and maintain you knowledgeable at this crucial second. Stand with the free press. Become a member today.

However now the courtroom seems prepared for one last lower, to kill off the final remaining piece of the act that enables the folks to problem racially discriminatory election practices.

On the night of Aug. 1, the courtroom launched its briefing query for rearguments within the case of Louisiana v. Callais, now referred to as Callais v. Landry. That query, which is supposed to instruct legal professionals on what subject is below debate, asked whether or not Louisiana’s “intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Structure.” This now units up arguments about whether or not Part 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the final remaining bulwark of the legislation post-Shelby County, is unconstitutional for requiring using race in some situations of redistricting. The courtroom will hear arguments on Oct. 15, early sufficient for a call that might impression the 2026 midterms.

Brynn Anderson by way of Related Press

Part 2 bans electoral practices that result in “a denial or abridgment of the correct … to vote” and that depart minority voters with “much less alternative … to take part within the political processes and to elect representatives of their selection” than white voters. Below the legislation, folks can problem electoral practices they imagine violate that legislation in courtroom, whether or not the practices allegedly infringe on voter entry or deny illustration by means of gerrymandering.

A call that declares Part 2 unconstitutional would depart the act toothless and threaten the existence of minority illustration, notably Black illustration, throughout the South.

“If this goes the way in which it seems prefer it’s going to go, it’s going to be Shelby County on steroids,” stated Nicholas Stephanopoulos, legislation professor at Harvard College. “That is going to be the only most catastrophic second for minority voters because the 1870s or Eighties.”

Louisiana v. Callais first got here earlier than the courtroom in 2025 as a part of a yearslong collection of Voting Rights Act instances stemming from the state’s 2021 congressional redistricting. The preliminary map adopted by the white- and Republican-dominated state authorities included only one Black-majority district out of seven, regardless of the Black inhabitants accounting for one-third of the state’s inhabitants. Black Louisianans introduced a Part 2 problem to the map, saying that it violated Part 2 by denying a second Black-majority seat when a cohesive and compact district could possibly be drawn. They received earlier than a three-judge appeals courtroom panel.

To adjust to the ruling, the Republican-run state authorities redrew its maps to accommodate a second Black-majority district, but it surely additionally used the event to shore up districts held by Republicans Speaker Mike Johnson and Rep. Julia Letlow. The brand new district took an odd form, stretching 250 miles from Shreveport to Baton Rouge.

A bunch of “non-African American” plaintiffs then challenged the brand new district for being drawn with an excessive amount of of a reliance on race: Whereas the Voting Rights Act requires race to be considered in sure situations, Supreme Courtroom precedent states that the consideration of race can’t be the principle issue, or else it might violate the 14th Modification’s Equal Safety Clause.

Each the state of Louisiana and the unique Black plaintiffs, represented by the NAACP Authorized Protection Fund, discovered themselves on the identical aspect defending the brand new district map. Louisiana claimed that the traces for the brand new district have been drawn in line with politics, a permitted issue, not race. The Supreme Courtroom heard arguments in March, on the time centering on whether or not race or politics predominated. However it selected to not subject a ruling by the top of the time period. As a substitute, it introduced that it might rehear the case with a brand new query to return. Now, we all know that query.

CHIP SOMODEVILLA by way of Getty Photographs

Even elevating the query of whether or not Part 2 of the Voting Rights Act violates the 14th and fifteenth Amendments has set off alarm bells within the voting rights group. One huge cause why is due to what Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in a concurrence for a really related case in 2022.

In Allen v. Milligan, the courtroom upheld a decrease courtroom ruling requiring Alabama to attract a second Black-majority district below Part 2 by a 5-4 vote. In dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas argued that, regardless of Congress’ reauthorization and updates to the Voting Rights Act, Part 2 can not proceed ceaselessly into the long run. Because the act was amended in 1982, no matter discriminatory practices that it was meant to treatment are not relevant 42 years later, he argued, so it will need to have an finish date because it “lacks any such salutary limiting ideas.” Kavanaugh concurred, including hints of what arguments future instances might deliver.

“The authority to conduct race-based redistricting can not prolong indefinitely into the long run,” Kavanaugh wrote. “However Alabama didn’t increase that temporal argument on this Courtroom, and I subsequently wouldn’t take into account it right now.”

Throughout oral arguments in Louisiana v. Callais in March, Kavanaugh was virtually completely targeted on this “temporal argument.”

“On equal safety legislation, the Courtroom’s lengthy stated that race-based remedial motion will need to have a logical finish level, have to be restricted in time, have to be a short lived matter. How does that precept apply to Part 2?” Kavanaugh requested.

And now the courtroom is re-hearing that case with the query of Part 2’s constitutionality raised.

“There’s a disagreement on the courtroom and so they wish to use this case to resolve that disagreement,” stated Justin Levitt, a legislation professor at Loyola Regulation Faculty.

If Kavanaugh’s “temporal argument” is on the coronary heart of this disagreement, then there might now be 5 votes to both vastly restrict Part 2’s attain or kill it completely. That would have a cataclysmic impression on minority illustration in Congress, state legislatures, metropolis councils, county boards and another workplace that depends on district line drawing.

“If this have been to occur it might imply that scores and scores of districts that everybody thinks at the moment are protected by Part 2 would not have any specific cause to exist the way in which they do,” Stephanopolous stated.

Simply have a look at what occurred after the courtroom disabled Part 5 of the Voting Rights Act in its Shelby County choice. Southern states, whose histories of discrimination required them to get modifications to voting insurance policies authorized earlier than enacting them, rapidly moved to enact restrictive voting guidelines. In North Carolina, a federal court found that GOP lawmakers had “goal[ed] African Individuals with virtually surgical precision” and struck down their election legislation below Part 2.

Part 2 was then, and continues to be now, an obtainable instrument for plaintiffs to deliver racial discrimination and dilution instances. In Shelby County, Roberts explicitly said that Part 2 remained a “everlasting” recourse for racially discriminatory actions even when Part 5 can be disabled. When Alabama and Louisiana redrew their maps in 2021, courts pressured them to redraw them with further Black-majority seats.

“If this goes the way in which it seems prefer it’s going to go, it’s going to be Shelby County on steroids. That is going to be the only most catastrophic second for minority voters because the 1870s or Eighties.”

– Nicholas Stephanopoulos, Harvard Regulation Faculty

However now the response to that Louisiana case threatens to finish what Roberts solely 12 years in the past referred to as “everlasting.” If the courtroom finds Part 2 to be unconstitutional, it might result in a racial model of what the nation is at the moment seeing with partisan gerrymandering after the courtroom stated that might not be litigated in federal courts in its 2019 choice in Rucho v. Common Cause.

Black and Latino majority districts throughout the South and past could possibly be worn out. Black congressional and state legislative illustration that boomed post-1965 could possibly be fully reversed with the elimination of the 11 Black majority districts, all held by Democrats, throughout GOP-controlled Southern states and numerous Black majority state legislative districts. If the courtroom holds that using race in drawing districts in any respect is unconstitutional, then these states would have free rein — even authorized justification — to eradicate these districts.

“We might rapidly see a return to all white congressional delegations and in state legislative chambers and native maps in lots of locations across the nation,” Stephanopolous stated. “This could be a a lot larger deal than Shelby County. It might apply nationwide.”

And whereas “the probably end result is a devastating end result,” based mostly on the truth that the courtroom is re-hearing this case with the brand new constitutionality query, in line with Stephanopolous. It isn’t a foregone conclusion.

“This is perhaps a really huge deal on the finish of the day, but it surely additionally may not,” Levitt stated.

There are any variety of off-ramps for the courtroom to absorb Louisiana v. Callais to keep away from hanging down Part 2. They might discover that politics predominated over race in drawing the brand new district, or that the state ought to merely redraw a brand new district that’s extra compact or prohibit using Part 2 with out killing it completely.

However these have been, by and huge, potential choices obtainable for the justices once they first heard the case this spring. As a substitute, they selected to re-hear the case with a brand new query.

“They’ve made a tough case for themselves out of nothing,” Levitt stated.

The tip consequence could be the finish of the Voting Rights Act and the total realization of consultant democracy it dropped at life over the previous 60 years. It might mark the nation stepping off that path towards American freedom.