Researchers found that moss spores can survive practically a 12 months uncovered on to house.

Regardless of intense UV radiation and temperature swings, most spores remained viable when returned to Earth. Their protecting casing acts as a pure defend, enabling resilience even scientists didn’t count on. The outcomes open doorways to utilizing hardy vegetation for future off-world agriculture.

Moss Resilience From Earth to Area

Mosses are recognized for his or her capability to flourish in a few of the harshest areas on the planet, from excessive mountain ranges just like the Himalayas to the scorching terrain of Demise Valley, in addition to the frozen Antarctic tundra and even the cooling surfaces of energetic volcanoes. Their outstanding toughness impressed researchers to ship moss sporophytes, that are reproductive constructions that comprise spores, into what would be the most inhospitable atmosphere of all: outer house. The research, printed in iScience right now (November 20), reported that greater than 80% of the spores endured 9 months exterior the International Space Station (ISS) and returned to Earth still able to reproduce. This marks the first documented instance of an early land plant surviving long-term direct exposure to space.

“Most living organisms, including humans, cannot survive even briefly in the vacuum of space,” says lead author Tomomichi Fujita of Hokkaido University. “However, the moss spores retained their vitality after nine months of direct exposure. This provides striking evidence that the life that has evolved on Earth possesses, at the cellular level, intrinsic mechanisms to endure the conditions of space.”

Fujita first began considering the idea of testing moss in space while examining plant evolution and development. Mosses seemed exceptionally capable of settling in places that challenge most forms of life. “I began to wonder: could this small yet remarkably robust plant also survive in space?”

A Radical Question: Could Moss Survive Space?

To explore this question, Fujita and his colleagues exposed Physcomitrium patens, also called spreading earthmoss, to a simulated space environment that included intense UV radiation, extreme temperature variations, and vacuum-level pressure.

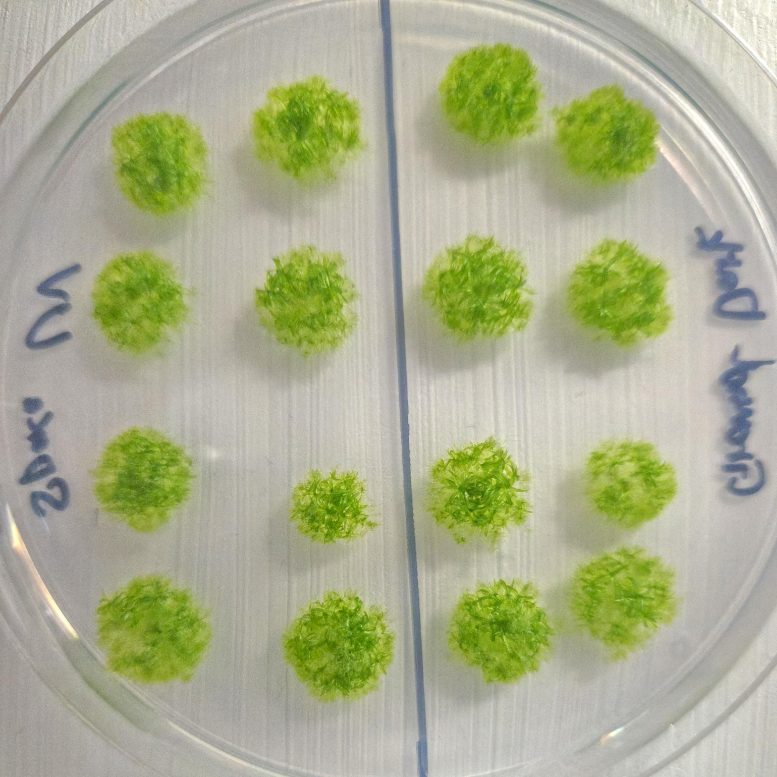

The team compared the survival of three moss structures: protenemata (juvenile moss), brood cells (specialized stem cells that form during stress), and sporophytes (encapsulated spores). Their goal was to determine which form had the highest resilience under space-like conditions.

Testing Moss Structures Against Extreme Conditions

“We anticipated that the combined stresses of space, including vacuum, cosmic radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and microgravity, would cause far greater damage than any single stress alone,” says Fujita.

Their results showed that UV radiation was the most damaging factor. Sporophytes were dramatically more resistant than the other forms. Juvenile moss died under severe UV exposure and extreme temperatures, while brood cells performed somewhat better. However, the spores inside sporophytes displayed ~1,000x greater UV tolerance. They also remained viable after enduring −196°C for over a week and after spending a month at 55°C.

Sporophytes Show Exceptional UV and Temperature Tolerance

The researchers believe the protective casing around each spore shields it by absorbing UV radiation and creating both physical and chemical protection for the spore within. They suggest that this adaptation likely helped early bryophytes—the plant group that includes mosses—move from aquatic habitats to land about 500 million years ago, enabling them to withstand multiple mass extinction events through Earth’s history.

To determine whether this natural protection would hold up in actual space conditions, the team then launched sporophytes beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Launching Moss Beyond the Stratosphere

In March 2022, hundreds of sporophytes traveled to the ISS aboard the Cygnus NG-17 spacecraft. Astronauts mounted the samples on the station’s exterior, exposing them to open space for a total of 283 days. The samples later returned to Earth on SpaceX CRS-16 in January 2023 and were brought back to the lab for examination.

“We expected almost zero survival, but the result was the opposite: most of the spores survived,” says Fujita. “We were genuinely astonished by the extraordinary durability of these tiny plant cells.”

Stunning Survival Results From the ISS

More than 80% of the spores lived through the entire trip, and all but 11% of those survivors germinated once they were returned to the lab. Tests on chlorophyll levels showed normal readings for nearly all pigments, except for a 20% decrease in chlorophyll a—a light-sensitive compound—yet this reduction did not seem to affect the spores’ health.

“This study demonstrates the astonishing resilience of life that originated on Earth,” says Fujita.

Wondering how long the spores might have lasted beyond the 9-month exposure, the researchers used their data to construct a mathematical model. Their estimate suggested that the spores could potentially survive up to 5,600 days, or roughly 15 years, under similar space conditions. They stressed that this is only a preliminary calculation and that additional experiments with larger sample sizes will be needed to refine those predictions.

The team hopes their findings encourage future work on how extraterrestrial soils might support plant growth and spark interest in using mosses to help build sustainable agricultural systems beyond Earth.

Toward Future Extraterrestrial Ecosystems

“Ultimately, we hope this work opens a new frontier toward constructing ecosystems in extraterrestrial environments such as the Moon and Mars,” says Fujita. “I hope that our moss research will serve as a starting point.”

iScience, Maeng et al., “Extreme environmental tolerance and space survivability of the moss, Physcomitrium patens”

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113827

This work was supported by DX scholarship Hokkaido University, JSPS KAKENHI, and the Astrobiology Center of National Institutes of Natural Sciences.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google, Discover, and News.