The picture streams over YouTube in crisp grayscale: a younger cahow — recognized outdoors Bermuda because the Bermuda petrel — scrambles by means of a sandy tunnel and pokes its tiny head above the bottom for the primary time. It’s just a few months previous, but it surely has by no means seen daylight. Grey fluffball hatchlings spend their entire lives as much as this second in a pitch-dark burrow so far as 15 toes underground. Now, in the course of the evening, this little fowl flaps and flexes its wings, perches on the fringe of a cliff, and launches itself into the wind. It gained’t contact down on land once more anytime quickly: a cahow’s first flight can final three to 5 years. Whereas it could relaxation on the water for a couple of minutes right here and there, it’s virtually totally airborne, zigzagging for a whole lot of 1000’s of miles throughout the Atlantic excessive seas, even sleeping while in flight. If it survives this odyssey, it’s going to come proper again right here — to this little speck of an outer island — touchdown as little as a yard away from the nest the place it was born.

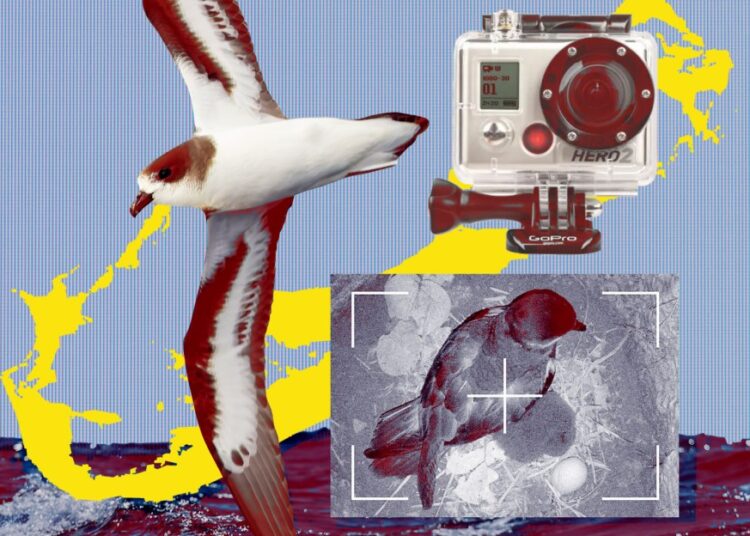

For hundreds of years, nobody knew this extremely uncommon fowl nonetheless existed. The cahow, Bermuda’s nationwide fowl, was assumed extinct for hundreds of years, and even after its rediscovery within the Fifties, its nocturnal life was a relative thriller. That’s, till a Bermudian conservationist with a proclivity for DIY electronics determined to hack a pair GoPros and arrange one of many earliest 24/7 livestreamed bird cams. There, he captured the unseen lifetime of this critically endangered “Lazarus” species — one of many rarest on Earth — for the primary time.

Right this moment, Bermuda’s Nonsuch Island is the center of the world’s solely cahow breeding floor, a protected 15-acre residence base to upward of 186 pairs. Jeremy Madeiros, warden of Bermuda’s Division of Surroundings and Pure Assets, does the hands-on work at this authorities nature reserve — monitoring nests, banding hatchlings, conducting well being checks, and tabulating the info. And in the event you’ve ever seen him talking about the way it’s going, it’s probably that Nonsuch Expeditions founder and filmmaker Jean-Pierre Rouja, the GoPro hacker, is behind the digital camera. For the previous 20 years, Rouja has been serving to doc the life and conservation of the Bermuda petrel — and piloting light-weight, scalable conservation tech within the course of, utilizing Nonsuch as his subject station.

Like many Bermudians, Rouja grew up following the rewilding work on Nonsuch. In 2005, he got down to make a documentary brief concerning the cahows’ comeback. His one massive drawback: the capturing circumstances have been removed from perfect. “They’re in darkish, man-made boroughs,” he says of the birds. “You’ll be able to entry them, however then you definately’re ripping the roof off their home, and also you’re not witnessing any pure conduct. We couldn’t afford to movie underground. It simply technically wasn’t potential on the time.”

By 2010, Rouja was completed ready round to see if somebody would invent the gear he wanted. “Principally, I ended up instructing myself,” he says of how he cobbled collectively the digital camera techniques he wanted — modular, waterproof, operable off the grid, in a position to auto-activate unobtrusively within the pitch darkish, with lighting that might be invisible to the birds, and to not point out accessible at a grassroots conservation pricepoint.

A self-described “pissed off electrical engineer” with no education in electronics, Rouja knew there could be trial and error. So he joined the “entire subculture” he discovered on-line of individuals hacking the comparatively new GoPro Hero, which he says have been “the one cameras I may afford to danger destroying.”

On a piece desk strewn with electrical tape, jeweler’s screwdrivers, wirecutters, and a scorching glue gun, Rouja cobbled collectively the customized digital camera system of his desires. He began by eradicating two GoPros’ IR filters, so they’d have the ability to decide up infrared underground. Then, he constructed his personal gentle arrays with particular person military-grade, 940-nanometer micro-LED bulbs, rigged with customized, laser-cut faceplates and transformers that might allow them to run off any energy supply (a automobile battery, for instance) within the wilds of Nonsuch. (He says wrote to GoPro, hoping for some type of sponsorship or accolades for his creativity. To his shock, the corporate wasn’t in any respect happy to listen to he’d discovered how one can flip its cameras into stealth spying gadgets — even when the topic of his surveillance was an endangered seabird. (GoPro has not responded to a request for remark on the time of this story’s publication.)

By 2011, Rouja and Madeiros had launched one of many world’s first 24/7 livestreamed wildlife cameras, elevating consciousness and delighting fowl nerds by sliding them neatly into the usual four-inch PVC pipes they’d constructed into the birds’ subterranean burrows, capturing the scene from above.

With most wildlife cams, Rouja says, “gentle is blasting on the fowl, and the fowl is trying in a field.” His cameras have been designed to permit viewers to not really feel like undesirable intruders. “We get very pure conduct,” he says. And regardless of the darkness, you’ll be able to see all of it vividly in black and white, right down to the main points within the feathers.

A several-year partnership with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology helped cement the livestream as a worldwide birders’ favourite. Finally rely, Rouja says, greater than 40 million minutes of cahow video had been watched.

The cahow cams proved enjoyable for spectators (and alluring for donors), however they’ve additionally pushed the analysis ahead. These birds are “elusive and troublesome to review,” as Madeiros puts it. Filming them across the clock permits the staff to “ground-truth” preexisting theories about breeding and conduct, Rouja says, and uncover new, wild truths within the course of.

Madeiros boats over to Nonsuch Island each few days. With the cahow cam, the staff can see all the things that occurs in between, from the odd however innocent storm petrel interloper (cahow cam watchers named him “Stormy”) that repeatedly made its approach into burrows trying (and failing) to woo and canoodle with cahow chicks, to the revelation of a symbiotic relationship between the cahow and one of many world’s rarest lizards, the Bermuda skink. (They cozy up with the cahows to maintain heat within the winter and reciprocate by scavenging to maintain the burrows tidy.) Final fall, the staff even caught a cahow in an act of infidelity on digital camera — and all of the drama that ensued.

Rethinking the price of conservation tech

To Rouja, the work on Nonsuch isn’t nearly saving one uncommon fowl species. He’s beta-testing conservation fieldwork tech that could possibly be put into play anyplace.

Most subject tech — satellite tv for pc trackers, thermal cameras, deep-sea sensors — was initially constructed for the navy, oil exploration, or industrial science. A single machine can price upward of $20,000. For many conservation initiatives, that type of price ticket is a legal responsibility, he says. “You want gear you’ll be able to afford to lose” as a result of “quite a lot of stuff you set out [in marine research] simply doesn’t come again.” Moreover, he says, that degree of sophistication is usually overkill. “The actual fact is that you could in all probability construct it for 300 bucks, or 500 bucks, relying on what it’s.”

“We’re utilizing Bermuda as a proof of idea to verify these applied sciences work, with the purpose of then with the ability to roll this all out at scale.”

The gen-one cahow cams have been proof of idea. Rouja is encouraging conservationists elsewhere to comply with his blueprints for remark of different underground species. Hawaii is probably going the following roll-out location for his nest cams. And because the cofounder of blue tech speedy growth facility Station B, he’s working with companions like Woods Gap Oceanographic Institute, Cornell, and MIT, testing and hardening gear for coral reef and ocean sensors, marine acoustics, and soundscape monitoring that he hopes might be inexpensive sufficient to deploy en masse.

For instance, if rats made it to Nonsuch and took maintain throughout nesting season, they may simply wipe out a complete technology of cahows and throw the delicate species off its monitor to restoration. To protect in opposition to this up to now, the staff relied on volunteers watching motion-detecting path cam livestreams all day and evening, in shifts. However now, they’re working with the Nature Conservancy to trial an AI-powered rodent detection system. For the previous 12 months and a half, human volunteers have been serving to prepare the Nature Conservancy’s machine-learning platform to distinguish between footage of innocent animals and threatening ones. Quickly, Rouja hopes, these cameras will automate the search, to allow them to spot a rat earlier than its presence would turn into a “catastrophe.”

“The cahow mission was my gateway into conservation tech with all of it now operating in parallel,” he says. “We’re utilizing Bermuda as a proof of idea to verify these applied sciences work, with the purpose of then with the ability to roll this all out at scale.”

Within the meantime, they’re up and operating on Nonsuch, the place a number of cahow cams might be streaming and recording this cahow hatching season in 4K HD, persevering with to broadcast a species’ journey again from the brink.